Ethics, Innovation & Creativity

I've always been drawn to the idea that the brush stroke represents the finger print of the artist, and by extension, the humanity behind the work. The importance of gestural marks serving as an artifact of humanity behind the creation, has, in the past, been a major attraction, and selling point, in contrast to a machined aesthetic, ‘clean’ and precise, and void of humanity. This is changing.

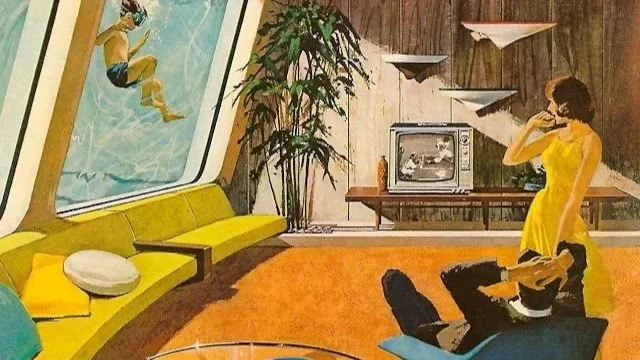

Just as the advent of Atomic Age in the 1940s and 50s sparked a re-evaluation of human creativity in the shadow of powerful new technologies, AI is forcing us to reconsider what traces of humanity we preserve in our work, or, in the workplace.

While the bulk of my work in innovation exposes me to ideas that serve the goals of efficiency, effectiveness, and organisational, and social problem solving, I am also deeply conscious that many new tools serve the goal of profit first, and humanity second, if at all. This is not new in innovation, and design is never agnostic.

I've been interviewed on several occasions on my thoughts about the impact of AI, and my insight leans heavily into my knowledge of current and historical innovation, leadership and culture, and my background in Critical Thinking, particularly ethics.

AI will be an incredibly valuable tool, we don't currently know the full scope of its ability or its true impact, but we do know that powerful tools in the wrong hands don’t serve humanity, and unfortunately, we are already seeing evidence of this direction. One recent example delivered during a townhall announcement on redundancies in the thousands, was a CEO proclaiming despite record breaking profits, 'don't worry, we'll still be number one, thanks to AI.'

This is why asking questions is so valuable, why reflection is important, why engaging with concepts like ethical fade or the categorical imperative, have real tangible meaning in the world today.

One example I use when discussing ‘ethical fade’ is based in how willing we are to seek/allow different decision outcomes when faced with the most minor inconvenience.

Some of you may be familiar with the ‘shopping trolly dilemma.’ Are you the kind of person who returns the shopping trolly to its allotted space, or do you leave it blocking parking spaces. Most people I meet will say, of course they return the trolley, it’s the right thing to do. As there are no real consequences, it’s a decision made in favour of a greater social good. Now add rain, add a screaming child in the car, add a long day, and a jar of Bolognese sauce falling and rolling under the car. This inconvenience usually leads to a different decision outcome. Something we once perceived as being of social importance, is now, more effort than it’s worth.

A simple example, but this plays out in the workplace too. In scenarios of similar low level importance. However, we are faced with an increasingly important ethical decision, the role of AI, and how it will impact work, how we work, and in many cases, who works, or whether we work at all.

These small compromises scale. Each decision we make, to prioritise speed or efficiency, or to avoid inconvenience, whether in dealing with a complicated work situation related to people, or the tools we use, may seem minor. It’s not easy to resist the pull of convenience, but if we don’t, we risk building a future where the brushstroke disappears entirely. The question is not whether tools of convenience will shape our world, but whether we will keep the occasionally inconvenient fingerprints of humanity on it.